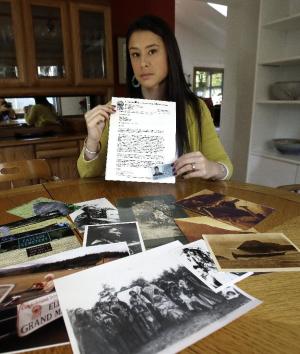

PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Mia

Prickett's ancestor was a leader of the Cascade Indians along the

Columbia River and was one of the chiefs who signed an 1855 treaty that

helped establish the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde in Oregon.

But the Grand Ronde now wants to disenroll Prickett and 79 relatives, and possibly hundreds of other tribal members, because they no longer satisfy new enrollment requirements.

Prickett's family is fighting the effort, part of what some experts have dubbed the "disenrollment epidemic" — a rising number of dramatic clashes over tribal belonging that are sweeping through more than a dozen states, from California to Michigan.

"In my entire life, I have always known I was an Indian. I have always known my family's history, and I am so proud of that," Prickett said. She said her ancestor chief Tumulth was unjustly accused of participating in a revolt and was executed by the U.S. Army — and hence didn't make it onto the tribe's roll, which is now a membership requirement.

The prospect of losing her membership is "gut-wrenching," Prickett said.

"It's like coming home one day and having the keys taken from you," she said. "You're culturally homeless."

The enrollment battles come at a time when many tribes — long poverty-stricken and oppressed by government policies — are finally coming into their own, gaining wealth and building infrastructure with revenues from Indian casinos.

Critics of disenrollment say the rising tide of tribal expulsions is due to greed over increased gambling profits, along with political in-fighting and old family and personal feuds.

But at the core of the problem, tribes and experts agree, is a debate over identity — over who is "Indian enough" to be a tribal member.

"It ultimately comes down to the question of how we define what it means to be Native today," said David Wilkins, a political science professor at the University of Minnesota and a member of North Carolina's Lumbee Tribe. "As tribes who suffered genocidal policies, boarding school laws and now out-marriage try to recover their identity in the 20th century, some are more fractured, and they appear to lack the kind of common elements that lead to true cohesion."

Wilkins, who has tracked the recent increase in disenrollment across the nation, says tribes have kicked out thousands of people.

Historically, ceremonies and prayers — not disenrollment — were used to resolve conflicts because tribes essentially are family-based, and "you don't cast out your relatives," Wilkins said. Banishment was used in rare, egregious situations to cast out tribal members who committed crimes such as murder or incest.

Most tribes have based their membership criteria on blood quantum or on descent from someone named on a tribe's census rolls or treaty records — old documents that can be flawed.

There are 566 federally recognized tribes and determining membership has long been considered a hallmark of tribal sovereignty. A 1978 U.S. Supreme Court ruling reaffirmed that policy when it said the federal government should stay out of most tribal membership disputes.

Mass disenrollment battles started in the 1990s, just as Indian casinos were establishing a foothold. Since then, Indian gambling revenues have skyrocketed from $5.4 billion in 1995 to a record $27.9 billion in 2012, according to the National Indian Gaming Commission.

Tribes have used the money to build housing, schools and roads, and to fund tribal health care and scholarships. They also have distributed casino profits to individual tribal members.

Of the nearly 240 tribes that run more than 420 gambling establishments across 28 states, half distribute a regular per-capita payout to their members. The payout amounts vary from tribe to tribe. And membership reductions lead to increases in the payments — though tribes deny money is a factor in disenrollment and say they're simply trying to strengthen the integrity of their membership.

Disputes over money come on top of other issues for tribes. American Indians have one of the highest rates of interracial marriage in the U.S. — leading some tribes in recent years to eliminate or reduce their blood quantum requirements. Also, many Native Americans don't live on reservations, speak Native languages or "look" Indian, making others question their bloodline claims.

Across the nation, disenrollment has played out in dramatic, emotional ways that left communities reeling and cast-out members stripped of their payouts, health benefits, fishing rights, pensions and scholarships.

In Central California, the Picayune Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians has disenrolled hundreds. Last year, the dispute over banishments became so heated that sheriff's deputies were called to break up a violent skirmish between two tribal factions that left several people injured.

In Washington, after the Nooksack Tribal Council voted to disenroll 306 members citing documentation errors, those affected sued in tribal and federal courts. They say the tribe, which has two casinos but gives no member payouts, was racially motivated because the families being cast out are part Filipino. This week, the Nooksack Court of Appeals declined to stop the disenrollments.

And in Michigan, where Saginaw Chippewa membership grew once the tribe started giving out yearly per-capita casino payments that peaked at $100,000, a recent decline in gambling profits led to disenrollment battles targeting hundreds.

The Grand Ronde, which runs Oregon's most profitable Indian gambling operation, also saw a membership boost after the casino was built in 1995, from about 3,400 members to more than 5,000 today. The tribe has since tightened membership requirements twice, and annual per-capita payments decreased from about $5,000 to just over $3,000.

Some members recently were cast out for being enrolled in two tribes, officials said, which is prohibited. But for Prickett's relatives, who were tribal members before the casino was built, the reasons were unclear.

Prickett and most of her relatives do not live on the reservation. In fact, only about 10 percent of Grand Ronde members do. Rather, they live on ancestral lands. The tribe has even used the family's ties to the river to fight another tribe's casino there.

Grand Ronde spokeswoman Siobhan Taylor said the tribe's membership pushed for an enrollment audit, with the goal of strengthening its "family tree." She declined to say how many people were tabbed for disenrollment.

But Prickett's family says it has been told that up to 1,000 could be cast out, and has filed an ethics complaint before the tribal court. They say the process has been devastating for a family active in tribal arts and events, and in teaching the language Chinuk Wawa.

"I have made a commitment to both our language and our tribe," said Eric Bernardo, one of only seven Chinuk Wawa teachers who also faces disenrollment. "And no matter what some people in the tribe decide, I will continue to honor that commitment."