PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Mia

Prickett's ancestor was a leader of the Cascade Indians along the

Columbia River and was one of the chiefs who signed an 1855 treaty that

helped establish the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde in Oregon.

But the Grand

Ronde now wants to disenroll Prickett and 79 relatives, and possibly

hundreds of other tribal members, because they no longer satisfy new

enrollment requirements.

Prickett's

family is fighting the effort, part of what some experts have dubbed

the "disenrollment epidemic" — a rising number of dramatic clashes over

tribal belonging that are sweeping through more than a dozen states,

from California to Michigan.

"In

my entire life, I have always known I was an Indian. I have always

known my family's history, and I am so proud of that," Prickett said.

She said her ancestor chief Tumulth was unjustly accused of

participating in a revolt and was executed by the U.S. Army — and hence

didn't make it onto the tribe's roll, which is now a membership

requirement.

The prospect of losing her membership is "gut-wrenching," Prickett said.

"It's like coming home one day and having the keys taken from you," she said. "You're culturally homeless."

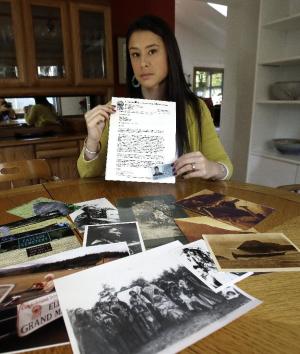

View gallery

Mia Prickett sits at a table with a collection of family photos and holds her Confederated Tribe of …

The enrollment battles come

at a time when many tribes — long poverty-stricken and oppressed by

government policies — are finally coming into their own, gaining wealth

and building infrastructure with revenues from Indian casinos.

Critics

of disenrollment say the rising tide of tribal expulsions is due to

greed over increased gambling profits, along with political in-fighting

and old family and personal feuds.

But

at the core of the problem, tribes and experts agree, is a debate over

identity — over who is "Indian enough" to be a tribal member.

"It

ultimately comes down to the question of how we define what it means to

be Native today," said David Wilkins, a political science professor at

the University of Minnesota and a member of North Carolina's Lumbee

Tribe. "As tribes who suffered genocidal policies, boarding school laws

and now out-marriage try to recover their identity in the 20th century,

some are more fractured, and they appear to lack the kind of common

elements that lead to true cohesion."

Wilkins,

who has tracked the recent increase in disenrollment across the nation,

says tribes have kicked out thousands of people.

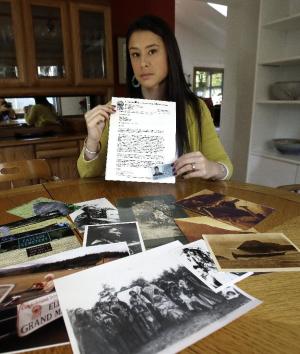

View gallery

Mia Prickett, middle, shares a collection of family photos with great aunt's Marilyn Portwood, r …

Historically, ceremonies

and prayers — not disenrollment — were used to resolve conflicts because

tribes essentially are family-based, and "you don't cast out your

relatives," Wilkins said. Banishment was used in rare, egregious

situations to cast out tribal members who committed crimes such as

murder or incest.

Most tribes

have based their membership criteria on blood quantum or on descent from

someone named on a tribe's census rolls or treaty records — old

documents that can be flawed.

There

are 566 federally recognized tribes and determining membership has long

been considered a hallmark of tribal sovereignty. A 1978 U.S. Supreme

Court ruling reaffirmed that policy when it said the federal government

should stay out of most tribal membership disputes.

Mass

disenrollment battles started in the 1990s, just as Indian casinos were

establishing a foothold. Since then, Indian gambling revenues have

skyrocketed from $5.4 billion in 1995 to a record $27.9 billion in 2012,

according to the National Indian Gaming Commission.

Tribes have

used the money to build housing, schools and roads, and to fund tribal

health care and scholarships. They also have distributed casino profits

to individual tribal members.

View gallery

Mia Prickett, seated on the floor holding a Confederated Tribe of Grande Ronde drum, poses for a pho …

Of the nearly 240 tribes

that run more than 420 gambling establishments across 28 states, half

distribute a regular per-capita payout to their members. The payout

amounts vary from tribe to tribe. And membership reductions lead to

increases in the payments — though tribes deny money is a factor in

disenrollment and say they're simply trying to strengthen the integrity

of their membership.

Disputes

over money come on top of other issues for tribes. American Indians have

one of the highest rates of interracial marriage in the U.S. — leading

some tribes in recent years to eliminate or reduce their blood quantum

requirements. Also, many Native Americans don't live on reservations,

speak Native languages or "look" Indian, making others question their

bloodline claims.

Across the nation, disenrollment has played out

in dramatic, emotional ways that left communities reeling and cast-out

members stripped of their payouts, health benefits, fishing rights,

pensions and scholarships.

In Central California, the Picayune

Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians has disenrolled hundreds. Last year,

the dispute over banishments became so heated that sheriff's deputies

were called to break up a violent skirmish between two tribal factions

that left several people injured.

In Washington, after the

Nooksack Tribal Council voted to disenroll 306 members citing

documentation errors, those affected sued in tribal and federal courts.

They say the tribe, which has two casinos but gives no member payouts,

was racially motivated because the families being cast out are part

Filipino. This week, the Nooksack Court of Appeals declined to stop the

disenrollments.

And in Michigan, where Saginaw Chippewa membership

grew once the tribe started giving out yearly per-capita casino

payments that peaked at $100,000, a recent decline in gambling profits

led to disenrollment battles targeting hundreds.

The Grand Ronde,

which runs Oregon's most profitable Indian gambling operation, also saw a

membership boost after the casino was built in 1995, from about 3,400

members to more than 5,000 today. The tribe has since tightened

membership requirements twice, and annual per-capita payments decreased

from about $5,000 to just over $3,000.

Some members recently were

cast out for being enrolled in two tribes, officials said, which is

prohibited. But for Prickett's relatives, who were tribal members before

the casino was built, the reasons were unclear.

Prickett and most

of her relatives do not live on the reservation. In fact, only about 10

percent of Grand Ronde members do. Rather, they live on ancestral

lands. The tribe has even used the family's ties to the river to fight

another tribe's casino there.

Grand Ronde spokeswoman Siobhan

Taylor said the tribe's membership pushed for an enrollment audit, with

the goal of strengthening its "family tree." She declined to say how

many people were tabbed for disenrollment.

But

Prickett's family says it has been told that up to 1,000 could be cast

out, and has filed an ethics complaint before the tribal court. They say

the process has been devastating for a family active in tribal arts and

events, and in teaching the language Chinuk Wawa.

"I

have made a commitment to both our language and our tribe," said Eric

Bernardo, one of only seven Chinuk Wawa teachers who also faces

disenrollment. "And no matter what some people in the tribe decide, I

will continue to honor that commitment."